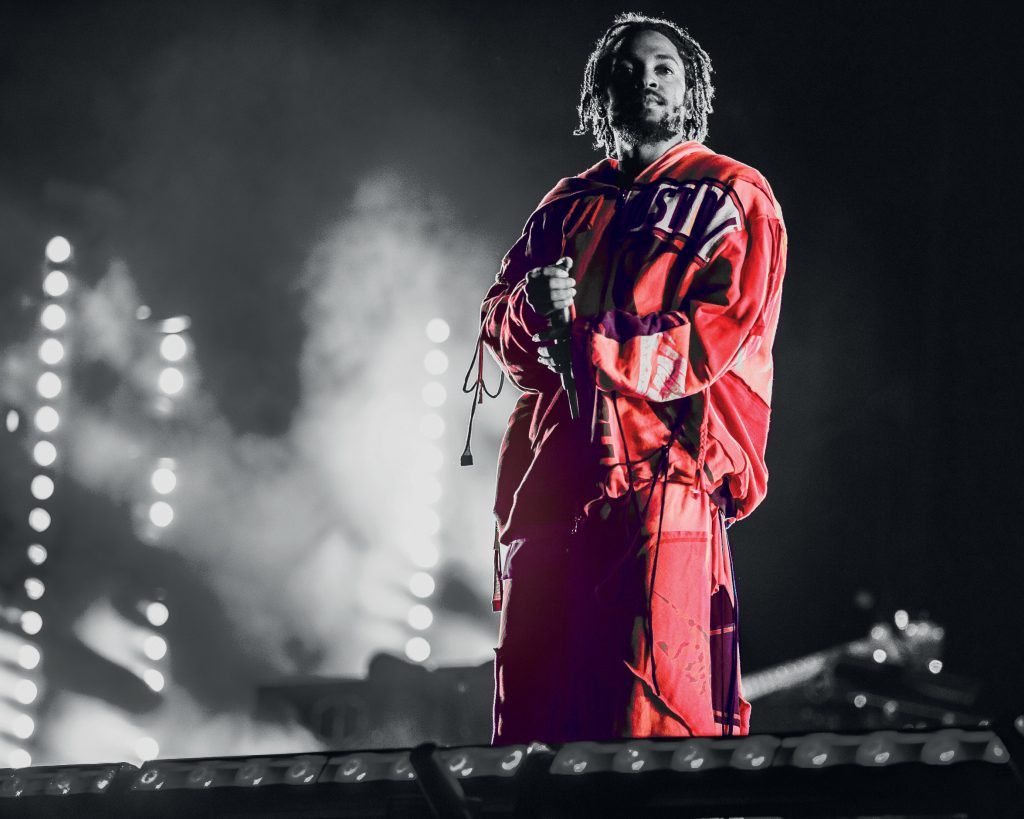

Kendrick Lamar has spent five years in the rap shadows. Now the genre’s defining voice is back to remind us all of his greatness.

The energy that exists in the space between the possessor of preeminent creative talent and the object through which that extraordinary gift is expressed is a fascinating place. It is charged with dormant potential, which is given life when the two touch. The space between Leonardo da Vinci’s paintbrush and the canvas. Lionel Messi’s boot and the football. Shakespeare’s pen and the paper. The space between Kendrick Lamar’s mouth and the mic. It’s been nearly five years since he has charged the space. His last studio album, Damn, was critically acclaimed. Lamar cleaned up on awards nights, winning a Grammy, his 14th, along with an American Music Award, a BET Award, and the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

The latter spoke to the quality of storytelling that defined Damn. That storytelling resonated because of its rawness, its realness. Lamar humanised himself to the audience. This demanded a depth of emotional intelligence that eludes rap’s Skkkrr Skkkrr generation. Appraising Damn, Interview magazine wrote: “But if it was Lamar’s soaring ambition and lyrical talent that made him particularly great, it is his honest introspection in verse and the clarity with which he has described his interior life that has made him sublime.”

Lamar has sat in the shadows as rap continued its rapid march away from intelligent storytelling and considered artistry, and towards a reality characterised by self-promotion birthed from fractured egos, poorly-veiled toxic masculinity, and delusions of rap grandeur. Now, he’s back to charge the space in ways that make him an ever-present in best-rapper-alive debates. Mr Morale and the Big Steppers, his fifth studio album, feels like rap’s, albeit temporary, redemption. “I spend most of my days with fleeting thoughts. Writing. Listening. And collecting old Beach cruisers,” Lamar wrote in a blog post describing his experiences in the five-year gap between albums. “The morning rides keep me on a hill of silence. I go months without a phone. Love, loss, and grief have disturbed my comfort zone, but the glimmers of God speak through my music and family. While the world around me evolves, I reflect on what matters the most. The life in which my words will land next.”

The people, specifically, his people, have always mattered most to Lamar. Speaking to iconic comedian Dave Chappelle for Interview magazine, Lamar summed this philosophy up. “At the end of the day, the music isn’t for me; it’s for people who are going through their struggles and want to relate to someone who feels the same way they do. I’ve got to go all-in, expressing myself, right there in the moment.” Africa has for some time been a muse to African-American creatives, so it came as no surprise that Lamar revealed to Chappelle that a trip to South Africa had been instrumental in helping hone his ability to connect with people.

CHAPPELLE: I know you’re a big Tupac fan. And Tupac used to talk about this phenomenon, as he got successful, but he was out of context. He’d say, “Where am I supposed to go? I can’t be around the ‘hood anymore, and they don’t want me in the Hollywood Hills. Where am I supposed to go?” Have you run into any altitude sickness from your ascent, fighting all the way up to where you are now?

LAMAR: I think I’m still growing. The more people I meet, the more cultures I start to embrace, the more people I open myself up to—it’s a growing process I’m excited about. But it’s also a challenge for me, to be at this level and still be able to connect with somebody who’s living that everyday life. At first it was something I struggled with, because everything was moving so fast. I didn’t know how to digest it. The best thing I did was go back to the city of Compton, to touch the people who I grew up with and tell them the stories of the people I met around the world. Making To Pimp a Butterfly was me navigating those experiences. I went to Africa and I was like, “This is something I can enjoy and something I can challenge myself with.”

CHAPPELLE: Was Africa your “Oh, shit, I made it” moment?

LAMAR: I went to South Africa—Durban, Cape Town, Johannesburg—and those were definitely the “I’ve arrived” shows. Outside of the money, the success, the accolades … This is a place that we, in urban communities, never dream of. We never dream of Africa. Like, “Damn, this is the motherland.” You feel it as soon as you touch down. That moment changed my whole perspective on how to convey my art.

That “shift in perspective” was a gift to rap. Indeed, Lamar has for some time been a jewel in the art form’s crown. Even at just 16, when he released his first mixtape, he was being hailed as a prodigy. His formative years were spent featuring on established rappers’ projects. Even then, his presence was power and his gift irrepressible. It sparked comparisons to Tupac, which grew ever deeper when he finally dropped his first solo album, good kid, m.A.A.d city in 2012. If that album registered him as a rap force, To Pimp A Butterfly set him apart as an artist who is able to explore depths of his creative gift in ways that most rappers, even some wildly popular ones, can’t. Damn then showcased his intellectual and artistic evolution in profound ways. It set him apart. Variety and Rolling Stone magazines declared him the voice of a generation. He shuns such tags, instead preferring to focus on metrics for success that others overlook. For example, Lamar ranks the track, Alright, as the most significant of his career.

It became the unofficial soundtrack of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.“You might not have heard it on the radio all day, but you’re seeing it in the streets, you’re seeing it on the news, and you’re seeing it in communities, and people felt it,” he told Variety. That has always been the defining characteristic of the world’s most gifted creatives – You don’t simply experience it at a surface cognitive level. You feel their work. Deeply. And it transforms critical dimensions of your human experience. This all starts with charging the space between their primary tool of creation and the object it affects most profoundly. It is charged with a touch. Brush to canvas. Boot to ball. Pen to paper. Mouth to mic.

Words by Ryan Vrede

Photography: Getty Images