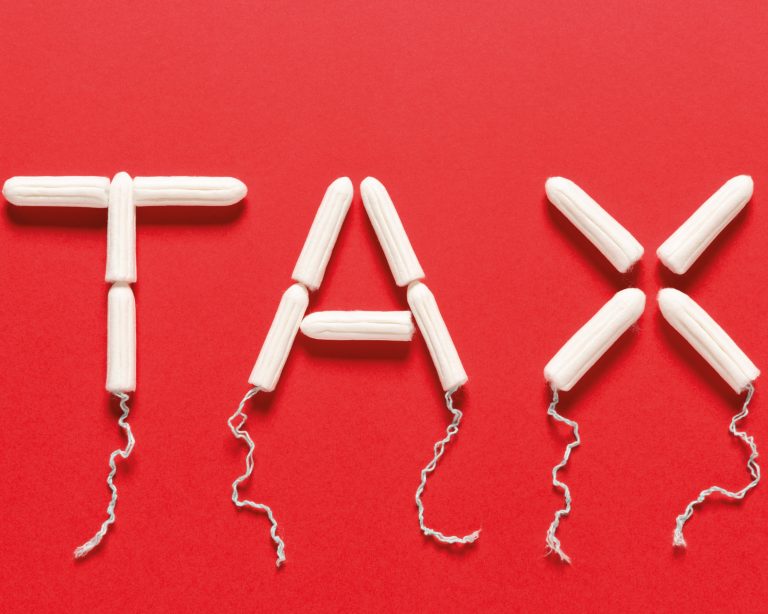

Sanitary products such as tampons and pads became zero-VAT-rated in South Africa back in 2019. But the question is, what did it take for us to finally get to THAT point – and how far do we still need to go?

THE STRIDES WE’VE MADE SO FAR

Fittingly, it was in his ‘maiden’ mid-term budget speech to Parliament, in October 2018, that Finance Minister Tito Mboweni finally announced that sanitary pads would be reclassified as a zero-rated VAT item from 1 April 2019. He also revealed that by way of increases to provincial budgets, sanitary products would be distributed for free to girls at public schools. This was the culmination of many, many years of campaigns, both here in SA and globally, ranging from the #BecauseWeBleed to the popular #TamponTaxMustFall. At the vanguard of the cause in South Africa, specifically, have been women’s rights advocates and a few legal bodies such as the Stellenbosch University (SU) Law Clinic, Femme Projects and Sheba Feminine – with the work of organisations including the social movement, Equal Education (EE).

In May 2018, the SU Law Clinic made a written submission to the independent panel of experts set up by the treasury to review the list of zero-rated VAT items, referring the panel to various constitutional rights such as the right to human dignity, which were being infringed on by adding VAT to feminine hygiene products. In the same month, Cosmopolitan South Africa ran an online petition that gathered more than 58 000 signatures. As the petition put it, the average woman is likely to spend up to R40 000 in her lifetime on period products. She will menstruate for about 40 years, with 13 periods a year, each lasting about five days and requiring two to six pads or tampons a day. That’s 260 pads or tampons a year – and 10 400 in a lifetime. At R1.50 to R3.80 per product, that amounts to anything between R15 600 and R39 520 overall.

But as laudable as that year’s scrapping of VAT may be, it’s a drop in the ocean when it comes to bringing relief and dignity to millions of those impoverished young women who simply can’t afford to buy these products at all. In real terms, it’s estimated to have brought down the price of pads at the cheaper end of the market by around R2 for a pack of 12, and at the higher end by around R4.50 for a pack of 16 maxi-pads. So while it’s a step in the right direction, dropping VAT is far from the end of the road – and the same holds true for increased allocations to provincial budgets.

STEP BY STEP

What most campaigners world-wide hope for is the provision of free sanitary products to all schoolgirls and students, as a way to address ‘period poverty’. This is an umbrella term for the lack of access not only to pads and tampons, but to menstrual hygiene education, hand-washing facilities, toilets, as well as waste-management services. It seems that here, too, South Africa has been making a few moves in the right direction. Former president Jacob Zuma first told ANC supporters in Polokwane on 8 January 2011 that sanitary towels would be provided to all women for free. After years of stalling on it (‘The matter was in front of Parliament’s multi-party Women’s Caucus for almost 10 years without progress being made,’ says Monja Posthumus-Meyjes, an attorney at SU Law Clinic), the Cabinet finally decided in October 2017 that free sanitary products should be piloted in KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga and the Eastern Cape ahead of a national roll-out at public schools.

Pads were first supplied for free in KZN, although concerns of the misspending of funds and poor quality of the pads were reported in March 2018. In March 2019, they were introduced in Mpumalanga.At the launch, then-Minister of Women in the Presidency Bathabile Dlamini stressed that few countries supplied free pads. Kenya was first, abolishing tampon tax in 2004, then both Kenya and Botswana began the provision of free sanitary products in 2017. And in the UK, tampon tax was only abolished at the start of 2021. However, Posthumus-Meyjes notes: ‘Of all the countries to remove VAT, I think we’re the only one that’s limited it to sanitary pads. This is short-sighted, and reinforces stigmas about the use of products that are inserted into our bodies.’

SANITATION AND HYGIENE CONCERNS

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2.3 million people globally live without basic sanitation services, and in developing countries just 27% have adequate hand-washing facilities at home, making it difficult for young girls and women to manage their periods. In South Africa, a 2015 Equal Education (EE) social audit found that 30% of high schools in Gauteng had more than 100 learners sharing a single working toilet, almost 70% of learners had no soap in their schools, and more than 40% had absolutely no access to toilet paper and/or sanitary pads. Unable to afford sanitary products, some use old rags, newspapers, sawdust or leaves, risking fungal and other infections. According to UNICEF, poor menstrual hygiene has been linked to reproductive and urinary tract problems.

A study by EE found that a lack of access to sanitary products resulted in girls missing school, affecting their education and ability to reach their full potential. Posthumus-Meyjes’ research on VAT on feminine hygiene products and the impact of high prices on those who can’t afford them, found that about 30% of schoolgirls stayed away from school when they had their period. This meant a girl could lose about 90 days of school a year, missing out on 30% of her education each year. ‘This places girls at a huge disadvantage,’ says Posthumus-Meyjes. ‘It’s a constitutional issue because human rights to education, freedom, security and human dignity are being infringed on. It’s a form of gender discrimination,’ she says.Posthumus-Meyjes made a valid argument. And in addressing this very issue, Minister Mboweni, in his mid-term budget speech back in 2021, outlined that: ‘R678.3 million is earmarked for provincial departments of Social Development and Basic Education to continue rolling out free sanitary products for learners from low-income households.

’However, a major concern still exists. The question: How is the public guaranteed that said funds are being used specifically for the purpose of providing sanitary towels, or even for any education purposes at all? Today in South Africa, an estimated 3.7 million girls are still unable to access menstrual hygiene products. Hopefully soon, free sanitary pad campaigns will be rolled out in every province, which the SU Law Clinic also urged in their report to the treasury. And then they, and others, can turn their focus to ensuring that all indigent women have access to free sanitary pads, not just schoolgirls. ‘SU Law Clinic also has great concerns about women attending tertiary institutions and needing access to sanitary products,’ explains Posthumus-Meyjes.

Words by Glynis Horning

Photography: Gallo/Getty Images, Courtesy Images